Yazidis in Germany: Don’t Deport - Negotiate

Shingal, 12 March 2018; (c) Carina Yıldırım-Schlüsing

Carina Yıldırım-Schlüsing, Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies (BICC) | Esther Meininghaus, Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies (BICC)

Since I arrived here, I haven't taken a moment off, I've always tried to educate myself, I've taken the language up to C1, and I've always worked. And then my Abitur was only recognised as a Fachabitur [technical diploma], so I'm doing my Abitur at an evening school. And I did everything I could to stay here, to find a home here. But they want to deport me – Alia Hassan (in HAWÁR Help, 2023)

2023 marks the year in which the German parliament unanimously recognised the genocide of the Yazidi population in Shingal (kurd.) /Sinjar (arab.) in Iraq: a genocide of a religious minority by the so-called Islamic State (IS, arab. ad-daula al-islāmīya) in August 2014. The genocide marked a horrific turning point for the entire Yazidi population: IS fighters attacked Yazidi men, women and children during and after the genocide, systematically committing mass murder, enslaving women and children, committing sexual violence, separating children from their parents and forcing them to live with IS fighters or selling them as slaves. They enforced conversion to Islam and subjected them to living conditions designed to bring about their slow death.

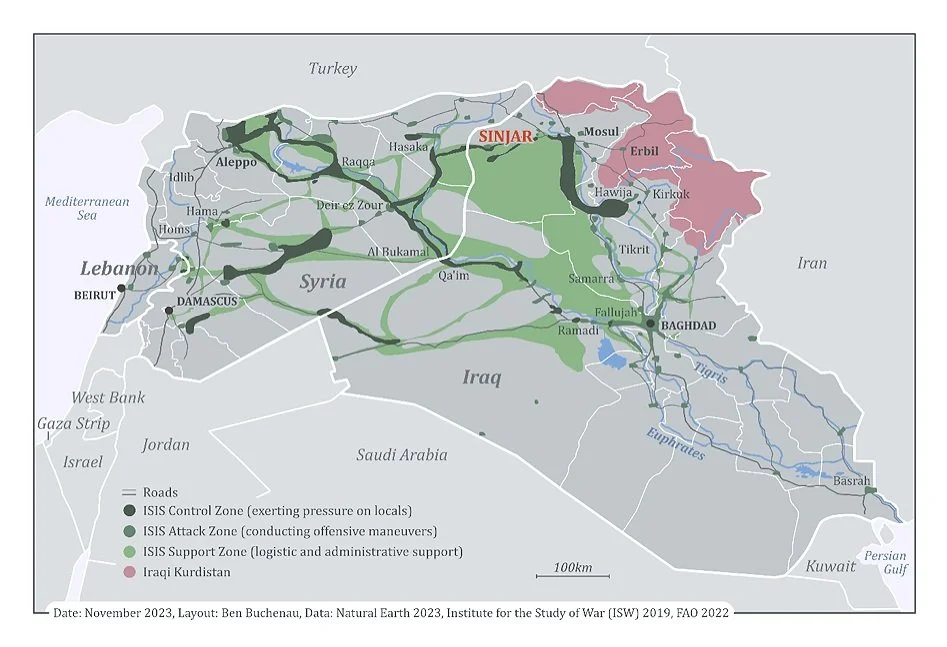

Because these actions were intended to erase the Yazidi identity and thus their existence as a community, the UN Human Rights Council declared that these acts constituted war crimes and genocide. The subsequent war against IS (2014–2017 in Iraq), which included air strikes on Shingal, one of the epicentres of the 2014 genocide alongside Kocho and Qinieh, destroyed around 80% of the town’s public infrastructure. Yazidi life in Iraq has since been uprooted, with many families having left the country or still living in IDP camps, mostly in the Kurdistan Region. There has been no significant return, particularly to the southern parts of Shingal due to insecurity and the lack of political solutions. Also, nine years after the genocide, IS has been defeated militarily but not ideologically.

2023 is also the year when German federal states have resumed deporting Yazidi families from Germany – i.e., returns against their will – either to countries of first arrival or back to Iraq. For weeks, Yazidis have been protesting outside the German parliament in Berlin, with some going on hunger strikes. So far, without success: On 20 November, a Yazidi family from Bavaria was separated when the parents and two of their children were forcibly relocated to Iraq. The deportation of Yazidi families who have built a life for themselves in Germany is not a responsible choice of policymaking but rather a sign of inconsistency, after the Bundestag’s recognition of the persecution of Yazidis in Iraq and the Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock witnessing the persistently difficult living conditions of Yazidis during her visit in March to Shingal. Instead of deporting individuals like Alia Hassan, who speak German and have trained hard to work, Germany can make a much better contribution by taking a proactive diplomatic stance and pushing for political solutions that allow Yazidis to return to Iraq safely, voluntarily and in dignity.

Fact I: Germany recognises persecution but actively deports

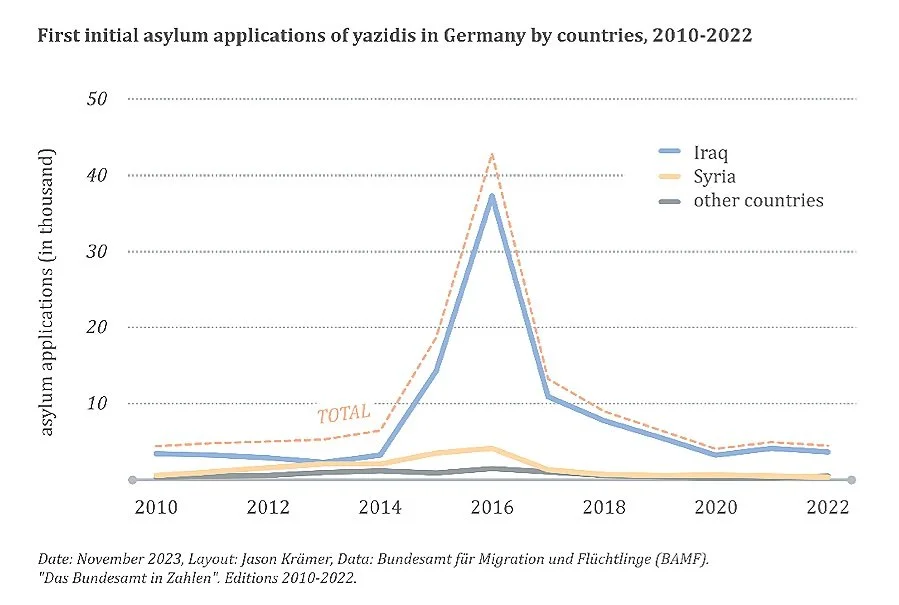

From a population estimated at around 700,000 before 2014 (interview, Duhok, 29/07/2017; Tagay & Ortac, 2016), many Yazidis fled Iraq, especially during and after the genocide in Ninewa. During this period, 65,749 Yazidis from Iraq applied for asylum in Germany, which is currently home to up to 200,000 Yazidis (Kanat, 2022), making it the largest Yazidi community outside of Iraq in the world. The German response to Yazidi asylum varies from one federal state to another. Baden-Württemberg, for example, introduced a special quota humanitarian admission programme in 2014 tailored to the needs of Yazidi women and children, many of whom had suffered rape, abduction, forced marriage and sexual slavery at the hands of IS (IOM 2023, p. 5). In its decision of 18 January 2023, the German Bundestag recognises:

The genocide against the Yazidis is still omnipresent in Iraq. More than 2,700 Yazidis are still missing. Mass graves are still being discovered. In addition, around 300,000 Yazidis are currently living in camps for internally displaced persons in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, in central Iraq or in Syria without the prospect of a safe return to their home region. Their safe return is hardly possible due to the highly volatile security situation that still prevails in Sinjar [...].

Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock, during her visit to Shingal, said:

Sinjar in northern Iraq, the original settlement area of the Yazidis: Here, it becomes clear why many people are still unable to return, even nine years after the genocide by IS. Their home has been destroyed.

Yet, since October 2023, cases of deportations of Yazidis have become public. So far this year, at least 135 Yazidis and non-Yazidis have been deported to Iraq. This is due to an unofficial agreement between the German coalition government and the Iraqi government to return people to Iraq. In 2022, Germany approved far fewer asylum applications, for instance 48.6% of applications by Iraqi Yazidis. Pro Asyl reports that between 5,000 and 10,000 Yazidis are currently at risk of deportation. The following findings come from the Committee for Human Rights and Humanitarian Aid (Ausschuss für Menschenrechte und humanitäre Hilfe):

Unlike in 2014 to 2017, the representative of the Federal Ministry of the Interior stated that the Yazidis as a group were no longer being persecuted in Iraq. However, the representative from the German Federal Foreign Office admitted that this assessment could only apply to a limited extent to the Sinjar and Dohuk provinces in northern Iraq. Repatriations would only take place to Baghdad. (16/11/2023)

But neither the assumption that deportations to Baghdad, where Yazidis have generally not lived before (but in Shingal), are safe, nor the argument that the persecution of Yazidis as a group does not exist, is correct.

Fact II: Iraq is not safe for Yazidis

Yazidis are not safe in Iraq. In the Shingal district, where most Yazidis lived before 2014, people today face a situation that, in many ways, has not changed since the immediate aftermath of IS atrocities in the area. Even after the official defeat of IS in December 2017, local politicians highlighted the massive lack of services, reconstruction and justice (interviews, Shingal, 12/03/2018). Yazidi residents stressed that some Arab families in the area, particularly from the Shammar tribe, fought to protect them from the IS onslaught and that they continue to maintain good relations. For the most part, however, the atmosphere in Shingal is one of fear, deep mistrust and persisting tensions, especially between Yazidis and Arab residents accused of identifying with IS. Most problematically, there has been little prosecution of IS atrocities, while many Yazidis have reported that public courts allow perpetrators to continue living in the area without being brought to justice:

We know that some of those who returned were with Daesh. They were supporting ISIS to occupy the area, to kidnap our women. So one of the reasons why we don’t trust these people again is that we know that they were here, and they know. We just ask them [the tribes] to give us the names of who is involved with ISIS or involved in what has happened to the Yazidis, but no one is helping us (interview, Dohuk, 24/01/2023).

Interviewees explain that Yazidis who file a case with the court are often threatened and forced to withdraw their case. This practice has recently increased. Furthermore, the ideological remnants of IS, that is Islamism and strong sectarianism that targets and persecutes Yazidis, continue to persist. Since IS’ official defeat, suicide-, IED- and SVIEB attacks claimed by IS against military targets and civilians have continued with varying intensity and IS is decentralising. In recent weeks, IS appears to be regrouping in eastern Syria on the border with Iraq.

The security situation in Sinjar is tightly controlled to prevent further attacks and also because various military and political actors want to prevent the return of Yazidis. Control of Sinjar is highly contested for geostrategic and economic reasons. Interviewees pointed out the assassination of local leaders—especially Yazidi—and frequent Turkish airstrikes on the area, which go largely unreported in the international media. Turkey operates a large military base in the Sinjar countryside, and the area is of great interest to armed groups with various foreign backing as well as to US and Iranian-affiliated militias, as one of the main roads links Sinjar to Syria in the west and Iran in the east. This road is known to be a major smuggling route (drugs, human trafficking, weapons and ammunition). At present, there is little open fighting, although interviewees reported that 10,000 people were newly displaced by fighting last year alone, and the area is often condoned off when there are fears of renewed clashes. Of the high number of IDPs, many face another winter in camps in the Kurdistan Region, unable to return. There are no security guarantees for the population in Shingal (interviews, Dohuk, January 2023).

Fact III: Re-traumatisation and deportations to Baghdad pose life-threatening risks

As mass graves continue to be excavated, around 2,700 of those abducted are still missing today (interview, Duhok, July 2017), and the engagement to bring back home those abducted continues. Trauma is the long-term consequence that Yazidis have to bear every day. According to Faisal Hamood Bashar (board member of the Cultural Association for Yazidis in Cologne), Yazidis have found safety and a second home in Germany (interview, 04/12/2023). Deportation to Iraq causes re-traumatisation. Dr Kamal Sido (Society for Threatened Peoples, background talk, 29/11/2023) and Faisal Hamood Bashar agree that Yazidis, who came to Germany years ago and have built a life here, should not be deported given the threats the community faces in Iraq.

Ways forward: Germany can engage diplomatically

Germany can and should engage pro-actively by using its diplomatic relations with Iraq and Turkey to work for an improved security situation for the Yazidi population in Iraq—no matter how much reluctance the German federal government will face.

Ways forward are, on the one hand, to push for a possibly revised Sinjar Agreement that considers bottom-up implementation and decision-making that is inclusive of Yazidis as called for by Yazidi stakeholders, as well as improvements that consolidate the remaining Yazidi life in Iraq, including an end to the killing of civilians from Turkish military attacks. On the other hand, continuing to provide a safe haven for those who have already rebuilt their lives in Germany is an imperative. Germany needs migrants like Alia Hassan, who are diligently working and pursuing education—deporting them or their family members is not the solution. The German government needs to implement a nationwide deportation ban for Yazidi men, women and children alike, prioritize protecting human rights and put its weight behind diplomatic negotiations.

Contact:

Carina Yıldırım-Schlüsing | Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies (BICC) | carina.schluesing@bicc.de

Esther Meininghaus | Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies (BICC) | esther.meininghaus@bicc.de